More on the conversation about "Conservatism 2.0"... I should point out that in this analysis, the new movement is meant to be an upgrade over the first generation of the "online right" (e.g. Drudge, Free Republic, Instapundit, etc.) -- in other words, the "1.0" implied here is not necessarily the whole post-Goldwater conservative movement per se. My own analysis, though, is that that whole movement is in fact at a crossroads, and that the challenge facing next generation activists like Patrick Ruffini and Soren Dayton is not just to redeem the movement of the 1990s, but to find a new logic for a coalition that was in fact assembled beginning in the 1950s. This means the problem goes considerably beyond issues of technology -- though Ruffini and Dayton seem to understand that.

Ruffini asks, "when does Movement 2.0 get started?" Do conservatives have to wait for Hillary Clinton to galvanize them? If so, why hasn't that begun to happen already? And just what is the conservative relationship to the Republican party these days? Dayton points out that, just as the online left is about "basic politics, constituencies, etc., rather than technology," so the new new right will need an organizing principle -- and he reviews a few possibilities. Ruffini responds with some agenda ideas of his own.

I want to comment on a few aspects of this exchange; I'll break up my thoughts into two or three posts. As with the Ruffini-Dayton discussion of a couple months ago, there are very real implications here as to what may become of our conservative political opponents over the next decade or two.

My first thought is on the question of whether Hillary Clinton can serve as an organizing catalyst for a movement -- whether any person can really do so -- and on how much significance lies in the difference between a catalyst and a principle. Ruffini writes that "opposition galvanizes political movements, and not just online" -- and I don't disagree. On the other hand, as he acknowledges, there hasn't been much galvanizing going on so far:

But a lot of folks also hoped that we’d be at least partly there by now. With Hillary looking good on the Democratic side, and Republicans in the opposition (and on offense) in Congress, have things gotten any better? Is there any evidence that the Stop Her Now stuff that was so effective in 2000 is working this time around? I haven’t gotten as many direct mail letters or fundraising e-mails with Hillary front and center as I would have expected by now.The other side of this coin is Dayton's assumption (shared with most of his conservative compatriots) that "opposition to Bush," or, in a more common phrasing, "Bush-hating," has worked as an "organizing principle" for the progressive netroots. As Dayton himself notes, such a "principle" is not the same thing as an actual idea.

By now the endless harping about "Bush-hatred" (the subtext is always: "irrational Bush-hatred") has grown stale enough that it's hardly worth the exercise of trying to parse and explain how liberals actually feel about the man and his administration. I'm content enough to reply that "Bush-hatred" is in fact a rational thing. Beyond that, the notions that people tend to personalize politics, and that "opposition galvanizes political movements," are basically truisms. It would be silly to claim that intense anger at George W. Bush hasn't helped fuel the growth of the new progressive movement -- both online and off (movements, plural, if you prefer).

I don't think I'm saying anything with which Ruffini or Dayton would disagree (other than the part about Bush-hatred being rational), and they seem to recognize that progressives have been working to lay far more durable foundations for our movement. Opposition can galvanize a movement, but it does not make a movement. Progressives are in fairly broad agreement on a number of policy fronts, among them the need for universal health care, for an end to the war in Iraq and a rational, multilateral foreign policy, for serious efforts to address the climate change crisis, for the protection of social security, for the preservation of the balance of powers and a more transparent, ethical government, and so on. Devotion to those ideas is precisely what fuels "Bush-hatred." Contrary to caricature, we don't all loathe the Bush administration because Dubya is a bumbling fake cowboy. We loathe it because it tramples on our principles and in so doing, in our estimation, seriously harms America.

I often get the sense that conservatives talking about "Bush-hatred" are projecting based on their own experience of Clinton-hatred during the 1990s -- making it all the more ironic that some of them seem to be waiting with bated breath for a chance to experience the hate all over again. But Clinton-hatred, I think, was a symptom of a decadent and confused conservativism. Some of it was no doubt fueled by rage at the Clenis (despite, or perhaps because of, the sick hypocrisy of so many of the president's prominent critics). But it really took off after the GOP's defeat in the 1995 budget showdown, and culminated in impeachment -- its purest and most impotent expression. Clinton-hatred was what the conservative movement turned to when it abandoned political philosophy. It amazes me that serious conservatives are nostalgic for it today.

One could defend conservatives, arguing that Clinton-hatred derived from the very sort of frustration I described liberals as experiencing -- that it was the product of a movement frustrated by its inability to legislate according to its own principles. Let's say we express all these frustrations affirmatively, as political ideas. What causes were lost to the conservatives, that drove them over the edge? Were they causes with which the majority of Americans would identify?

If politician-hatred is ultimately a manifestation of frustration over thwarted principles, perhaps it's better to lay our principles on the table. Again, progressives have health care, an end to the Iraq war, etc. What do conservatives have? Are they politically viable ideas? This is where Ruffini and Dayton turn next. In the meantime, I'd suggest that anyone looking to Clinton-hatred to kickstart Conservatism 2.0 isn't addressing the root challenge facing the right.

Labels: conservative futures, George Bush, Patrick Ruffini, Soren Dayton

Bob Kaufman calls it "moral democratic realism," and is apparently seeking to salvage some kind of legacy for it. George Weigel approves.

Says Kaufman:

Moral democratic realism offers a ..compelling framework for American grand strategy...because it takes due measure of the centrality of power and the constraints the dynamics of international politics impose, without depreciating the significance of ideals, ideology, and regime type. It grounds American foreign policy in Judeo-Christian conceptions of man, morality, and prudence that innoculate us against two dangerous fallacies: a utopianism that exaggerates the potential for cooperation without power; and an unrealistic realism that underestimates the potential for achieving decency and provisional justice even in international relations. It rests on a conception of self-interest, well understood, and respect for the decent opinions of mankind, without making international institutions or the fickle mistress of often-indecent international public opinion the polestar for American action...Weigel compares this approach to the old "Catholic International Relations" theory of America and Commonweal. He seems to find in it some kind of appealing middle ground:

Kaufman rightly rejects alternative grand strategies on prudential grounds. Isolationism of the Pat Buchanan sort ignores the lessons of history and, to our eventual endangerment, abandons any American commitment to helping build order out of chaos in the world. Neo-realism (think Brent Scowcroft, James Baker, and most of the permanent State Department bureaucracy) imagines that messes like the Middle East can be managed by manipulating "our thugs;" yet this is precisely the approach that helped create conditions for the possibility of 9/11. Jimmy Carteresque multilateralism is hopelessly unrealistic, and thus dangerous.We are presented with the argument that this Bush-derived theory of IR means detatching American policy from thuggery: risum teneatis, as images of Gitmo and Abu Ghraib and extraordinary rendition and all the rest come to mind, and the words of their neoconservative defenders echo in our memories. And we are meant to believe, after the utter debacle of unilateralism in Iraq, that it's the traditional multilateral approach (the approach that won the cold war) which is somehow "hopelessly unrealistic"? One wonders whether distinguished academics like Kaufman and Weigel have paused at any point during the past six years to peer out from their ivory towers onto the landscape of the real world. Perhaps they have been too busy doodling in their notebooks, coming up with grand-sounding phrases like "moral democratic realism," which, in case no one else has already made the joke, I would suggest sounds neither moral, nor realistic (the "democratic" aspect of it is probably neither here nor there).

Still, take note: the Bush doctrine, that recipe for catastrophe, continues to have its defenders, and they are determined to refine it into a permanent school of conservative international relations theory.

Labels: Bob Kaufman, Foreign Policy, George Bush, George Weigel

David Brooks writes a column about George W. Bush's child-like devotion to his own failed war policy. This is not delusion, says Brooks:

Rather, his self-confidence survives because it flows from two sources. The first is his unconquerable faith in the rightness of his Big Idea. Bush is convinced that history is moving in the direction of democracy, or as he said Friday: “It’s more of a theological perspective. I do believe there is an Almighty, and I believe a gift of that Almighty to all is freedom. And I will tell you that is a principle that no one can convince me that doesn’t exist.”This graf sets off a chain of reaction from conservative writers who are ready to pronounce themselves fed up with Bush's self-aggrandizing theological fantasies. Andrew Sullivan writes:

[A]s a political or historical principle, this is dangerous, delusional hogwash. There is a distinction between theology and politics, a distinction between theory and practice: distinction at the core of the very meaning of conservatism. The notion that free will or even human freedom is destined to be humanity's future, and that this destiny can be achieved by a Supreme Leader, is a function not of conservatism in any sense, but of a messianic, eschatological ideology.Bush, says Sullivan, is not a conservative statesman; he is a "delusional fanatic:"

If you define liberalism broadly as the belief that human society is perfectible, that heaven can be created on earth by force of will, then Bush is one of the most recklesss enemies of conservatism who has ever held high office in America.Rich Lowry thinks it sounds suspiciously liberal, too:

Bush believes the spread of liberty is "inevitable." If that is the case, why not spare ourselves all the effort and let the inevitable flowering of liberty take hold? Now, he does say that there will be different expressions of liberty and a different pace—"but we've all got the same odds of achieving the same result." That strikes me as flat-out wrong, an otherwordly leveling of all the culture and history that separates various societies.Rod Dreher says Bush is "living in a dream world," in thrall to a "social engineering ideology [which] is anti-conservative to the marrow:"

Well, look, I believe there's an Almighty too, and that He desires his human creatures to live in freedom. But good grief, you can't start wars based on that messianic principle, and continuing them on the same grounds!Ross Douthat is a bit more vehement:

I'm fed up with the President's messiah complex, and I don't bloody well want to hear any more about Bush's "theological perspective" that freedom is the Almighty's gift to all mankind, and so history's on our side in the Middle East, and yada yada yada.Douthat also emphasizes the distinction between theology and politics:

The gift of freedom that Christ promises is far more real than anything else in this world, if Christian teaching on the matter is correct. On the other hand, there's nothing that's political about that promise, and the attempt to transform God's promise of freedom through Jesus Christ into a this-world promise of universal democracy is the worst kind of "immanentizing the eschaton" utopian bullshit.All of this is very interesting: it's a return to a sort of ur-conservative thinking; it's a revival of Burke in an era when the American right has been driven by a very un-Burkean revolutionary zeal. One of the key tenets of traditional conservatism has been its mistrust of politics. As Burke said:

Wise men will apply their remedies to vices, not to names; to the causes of evil which are permanent, not to the occasional organs by which they act, and the transitory modes in which they appear. (Reflections on the Revolution in France)Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously defined it thusly: "The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society."

From the traditional conservative view, an over-emphasis on politics as opposed to culture means social engineering at home; Wilsonianism and "nation-building" abroad: all of these things are to be abhorred. But the modern conservative movement, the movement that ultimately brought Bush to power (even if it mistrusted him) succeeded because of its political skill and innovation. The movement has talent for politics, and an instinct for it, and we should hardly be surprised to find that that instinct has eventually found its way into its foreign policy. This is not, in fact, Wilsonianism; it is the traditional interests and preoccupations of the conservative classes cross-bred with a distinctly un-Burkean aggressiveness. That it has learned to broaden its appeal by using Wilsonian language should not distract from its essential nature.

Even when the movement has emphasized culture as a pre-political concern, it has been more Gramscian than Burkean, waging an aggressive war of position to further a transformative agenda that the movement itself understands is too radical for the tastes of most Americans.

This is not to let American conservatives escape by creating a distinction between Bush and "true" conservatism. That's a political version of the "no true Scotsman" fallacy; we didn't accept such excuses when Marxists made them and there's no reason we should accept them from conservatives. American conservatism is what it is, and there are undoubtedly reasons why it seems so frequently to escape the careful bounds of Burkean wisdom. One possible reason is that the United States is not a Burkean state; it is a liberal, constitutional regime, whose legitimacy is derived from popular sovereignty and a dedication to upholding the natural, abstract rights of human beings. Ramesh Ponnuru, in the same debate discussed above, reminds us of this, when he cautions:

Now it may be unconservative to think that an aggressively liberty-promoting foreign policy follows from the idea that all human beings have a God-given right to be free, and certainly Christians are not obliged to believe that it does so follow. But the proposition that our rights are a gift from God is neither un-conservative nor un-Christian; it is a commonplace observation in the context of American political history.A couple of notes here: for one thing, when Ponnuru says that the observation is not "un-conservative," it is "in the context of American political history." Conservatism in the context of American political history is something very different from conservatism in other contexts. It's a conservatism rooted partly -- but not wholly -- in a devotion to the very kind of liberal order to which conservatives once defined themselves as opposed. This creates all sorts of odd effects, including especially the strange American conservative relationship to politics, which is often enthusiastic but tortured, destructive, and prone to inspire bouts of conservative self-loathing like the ones witnessed above.

The other note, and what should have become apparent here, is that I don't think this is really a debate about theology at all: it's about politics. When these commentators talk about Bush's "messianism," they may be referring to religious expression in an immediate sense, but in more significant sense they're talking about the frightening effects of a conservatism that has too readily embraced politics. The dramatic irony is that they can see the tragic results of such an embrace, but as American conservatives they can't quite disentangle themselves from its legacy.

Labels: conservatives, George Bush

By now you may have read the big article in the Washington Post, examining the state of a failed president who is too self-absorbed to feel as beleagured as he actually is. At this point, the article tells us, Bush is focused on Iraq to the exclusion of everything else, convinced that his legacy will ride upon that war alone.

Matt Yglesias reminds us that, arguably, his legacy lies equally in his extraordinary failure to have a legacy, particularly in domestic matters:

It's also true that for a two term president who enjoyed GOP congressional control for several years, he really does have remarkably few legislative accomplishments. Where other leaders would have seen an opportunity to push a governing agenda, Bush saw an opportunity to evade congressional oversight as he used the executive branch to commit crimes against the constitution, fill many executive agencies with incompetents, and fill others with people who helped his campaigns' financial backers rob the public. Which leads us to what's probably the most important aspect of Bush's non-Iraq legacy, his decision to provide an elegant demonstration of public choice theory and destroy public faith in the possibility of government action by showing exactly how poorly a government can be run.Yglesias goes on to list some of the failures.

Compassionate conservatism, it seems to me, was the theory behind a potential agenda. But therein lies another legacy: our debate over why it failed as a governing philosophy. Because Bush wasn't sufficiently committed to the actual policies the campassiocon theorists prescribed? Because he was too incompetent to implement them properly, or to sell them to the public? Because ideas matter less to conservative elites than opportunities to enrich their friends and strip away irritating regulations? Or because they really weren't very good ideas to begin with?

Labels: compassionate conservatism, George Bush

I read Naomi Wolf's "Fascist America, In 10 Easy Steps" with great interest. Wolf lucidly recounts a number of the Bush administration's sins against American democracy -- from Gitmo to the politicization of the bureaucracy to the equation of dissent with treason -- arguing that "we need ... to look at the lessons of European and other kinds of fascism to understand the potential seriousness of the events we see unfolding in the US." I certainly don't want to discount the seriousness of those events, but I do want to take issue with the use of "fascism" as descriptive term for their cumulative significance.

Norman Geras identifies the flaw in Wolf's argument:

[D]espite her talk of dictatorship and her several allusions to fascism, Wolf has a couple of qualifying sentences registering a different awareness. Thus:What Geras means, of course, is that you shouldn't call something fascism if you don't believe that it really is fascism. The term has a particular historical and political meaning, and while Wolf correctly identifies a list of outrageous anti-democratic administration practices, she herself seems to recognize that what they add up to is something rather different than what Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler were all about.Of course, the United States is not vulnerable to the violent, total closing-down of the system that followed Mussolini's march on Rome or Hitler's roundup of political prisoners. Our democratic habits are too resilient, and our military and judiciary too independent, for any kind of scenario like that.These sentences might be taken as showing that Wolf doesn't fully believe her own case.

Given the gravity of the Bush administration's offenses, this may seem like a pendantic point. It isn't. I recognize that hyperbolic rhetoric may be our first line of defense against the erosion of Constitutional freedoms, and if that is therefore the rhetoric we have to employ in certain situations, so be it. But can we at least whisper among ourselves about what might be a more precise analysis? Foreign readers can interpret our politics however they want; American progressives have a responsibility to hold to a more clear-headed understanding of what our conservative foes are actually doing. If conservatives are not actually on the road to fascism, but to something else, shouldn't we figure that out -- the better to head them off at the right pass?

Fascism, a 20th century European political practice sometimes imitated by tyrants in the developing world, is not the only alternative to constitutional democracy. And it's not what the Bush administration is trying to construct. Frankly, fascism is too collectivist, even just too organized for these people. The thing is, you can look around the world right now and see examples of states that are neither fascist nor particularly democratic. The two most powerful nations in the world after the U.S. are cases in point. And while certain social conservatives would no doubt be perfectly comfortable with a Christian version of Iran's Islamic Republic, Putin's Russia might represent a more accurate nightmare scenario for what the Bush administration would let America become: an authoritarian quasi-democracy ruled by gangster capitalism and just enough political intimidation to keep the right people in power without necessitating stormtroopers in the streets. Of course, Russia doesn't have the tradition of democratic institutions that Wolf cites as America's own insurance policy.

That does not, of course, mean we shouldn't guard against the erosion of those institutions. But to what purpose are they being eroded? Bush and Rove have constructed a political machine meant, like every other political machine in American history, to keep their faction in power as long as possible. They've abandoned the traditional Republican hostility to a strong executive and sought to push the boundaries of the politicization of bureacracy, society, and media. Like most administrations -- only moreso -- they have pushed to keep the Constitution from standing in the way of their political aims. In all of this they have been unusually vigorous and effective, which is cause for a great deal of concern. But they are not the vanguard of a fascist movement -- they're not even particularly well-liked in the conservative movement. Their project is not to create a fascist state, but to loosen the various restrictions imposed by custom, discourse, and the Constitution on their political freedom of movement.

The conservative movement undergirding the modern Republican party has varying and often conflicting goals. Parts of it are primarily concerned with eliminating regulatory regimes that various industry lobbyists, in their perpetual shortsightedness, think of as limiting American capitalism. Parts of it want to legislate morality, to greater or lesser extents. Parts of it advocate vigorous intervention abroad; parts of it denounce American imperialism.

As with the Bush administration, big-picture thinking is far less important to the conservative movement than appearances might suggest. The primary political imperative is to move immediate obstacles out of the way, to advance whatever might be the mission of the day. Unfortunately, those obstacles often tend to be rather important features of American democracy.

The effect of all this, if left unchecked, will be to degrade that democracy and gradually sink the United States from the ranks of advanced, liberal Western nations. It could make the U.S. more vulnerable to charismatic authoritarians; it would undoubtedly weaken our public infrastructure and erode our quality of life. While it could lead to more aggressive militarism abroad, it would be just as likely to undermine America's capacity for adventurism (or, on the other side of the coin, our capacity for international leadership).

Fascism is a sort of constructive nihilism. It builds; it wants more. What the Bush administration and the conservative movement would leave to us is America, but less so.

Before we had fascism as a metaphor to call upon, America went through similar periods of degradation. The Alien and Sedition Acts. The vicious anti-Constitutional crackdowns during the First World War. The Red Scare. Internment. We didn't become a totalitarian state; we continued to be America -- but less so. It fell to progressives in subsequent eras to set the country back on a better course; the tool they used to accomplish this was American democracy. That's why I disagree with Tristero of Digby's blog on this. Says Tristero:

Call America's national government and dominant media whatever you will; it's pointless to quibble over labels. Except in one instance. This is no longer a democracy.It's not a pointless quibble to demand precise analysis of our political situation. And it's simply absurd to claim that "this is no longer a democracy." This is a democracy -- only less so, for the moment. The way to rectify the conservative degradation of America is to remember that we are a democracy, and to act accordingly.

Labels: conservatives, fascism, George Bush, Naomi Wolf

After six and a half exhausting years, it seems strange to remember that when George W. Bush hit the campaign trail in 2000, he ran not as an ideologue, but as something of a cipher. There was no talk of grand schemes to bring democracy to the middle east, no bragging about a permanent Republican majority. Bush's major campaign pledges seemed to involve not sleeping with interns and healing the vicious partisanship his own party had done so much to create. In the estimation of many analysts - left and right - there was little to separate the Texas governor from his Democratic opponent.

His candidacy seemed appropriate for a Republican party uncomfortable in its own ideological skin. As libertarian author Ryan Sager tells it, after their disastrous 1995 showdowns with President Clinton over Medicare and the budget, Congressional Republicans had fallen victim to a kind of "Vietnam syndrome," abandoning their own agenda and spiraling into an impotent rage that led them, against their own better judgment, into the impeachment fight. Meanwhile, their electoral fortunes waned. The party's 1996 presidential nominee was the favorite of neither economic conservatives (that was Forbes), nor social conservatives (Buchanan). He was a grey and uninspiring Senator who simply happened to be next in line. That year and in 1998, voters cut away at the GOP majority; by the end of the Clinton presidency Republicans seemed to stand for little but vindictiveness and unctuous sexual moralizing. Even their one significant accomplishment - dismantling AFDC - had been cast as a victory for the Democratic president.

It was in this context that the 41st president's son took to the podium in Philadelphia, in August 2000, to claim his party's nomination for chief executive. Democrats mocked the Republicans for putting more people of color on stage at that convention than ever seemed to vote the GOP line; what observers across the ideological spectrum failed to grasp, though, was how that decision, and the apparently "centrist" rhetoric of the campaign that followed, were carefully conceived elements of a strategy to revitalize and reassert a distinctly conservative politics. In retrospect, it seems more egregious that most analysts missed the significance of Bush's choice of foreign policy advisors, but a careful examination of his domestic policy team, too, might have indicated something of how ambitious a Bush administration would turn out to be.

Instead, after a scandalously resolved election, most observers would have agreed with Daniel Casse, when he wrote in the March 2001 issue of Commentary that, even before the inauguration, "George W. Bush already seemed a man condemned to a presidency of limited expectations" (pp. 19-24). We have come to view the attacks of the following September 11 as the history-altering moment that unleashed the Bush administration's ideological demons. While those events undoubtedly changed the political context in the president's favor, Casse's article, titled "Bush and the Republican Future," demonstrates how those "limited expectations" failed to reflect the true breadth and meaning of the new administration's ambitions - the agenda Bush's team had been preparing since well before the election.

Casse does not understate the dilemma facing Republicans at the turn of the century. "Bush's victory," he says, "could be viewed as marking not the beginning of a new, post-Clinton era but as the last gasp of an earlier one -- the era of muscular, confident, conservative Republicanism." Just as mainstream pundits of the 1990's warned Democrats away from economic populism, so they forecast doom for the Republican party if it failed to, in the words of the New Republic's John Judis, "jettison the socially conservative base it gained during the 80's." This particular analysis aside, Casse agrees that

[T]here is no denying that the GOP has indeed become a party in decline. Many of the issues and conflicts that energized Republicans over the past twenty years have dissipated or disappeared altogether. Even more significantly, from the perspective of presidential politics, the electoral coalition that emerged at the end of the 1970's to sweep Ronald Reagan into office no longer exists in any meaningful form.To Casse, this state of affairs came about in part because the conservative priorities of 1980 had largely been addressed:

The Soviet Union collapsed. Taxes were cut. Confidence returned. The federal budget was balanced. In time, the party's libertarians and cultural conservatives drifted off to pursue other, sometimes conflicting, political agendas.A neutral observer might point out that Reagan in fact left massive structural deficits, and that while he made government meaner, he in no sense made it leaner, failing -- as we've discussed in other posts -- to achieve any significant transformation of American political economy. But such criticisms are beside the point. Casse is describing the breakdown of the fusionism that had bound the conservative movement before and during the Reagan years; like Sager, he understands the failures of the Buchanan rebellion and the Gingrich revolution as being both causes and effects of that process. At the center of the breakdown, though, was a policy problem: "tax cuts, once the signature issue of the party, were no longer the galvanizing force they had earlier been." Clinton's stimulus package had both fueled the economic recovery and wiped out the marginal tax cuts theretofore cited by Reagan's supply-siders as their most significant victory. Bob Dole's tax cut proposals had failed to impress the voters, and Republicans, who had once dreamed of totally overhauling the federal tax code, were reduced to advocating "a few incremental measures" like eliminating the estate tax. And the philosophical rot at the heart of the conservative coalition was spreading:

Yet if tax cuts had lost their force as an issue, the party was also unable to come together on much else. Preparing to select a nominee for the 2000 election, the GOP could boast no internal consensus on how to reform Medicare or Social Security, and no single view on what to do with the growing federal budget surplus. Within the party, there were bitter divisions over foreign engagement and military spending. On abortion, trade, immigration, debt reduction, and antitrust policy, no unity was to be found.Bush seemed unlikely to resolve these uncertainties. In a party whose vestigial ideological camps were the flat-taxers and the Buchananites, Bush was neither. Rather than promising a firm ideological hand, he seemed to project his candidacy as something moderate and humble. As Casse puts it:

[A] plausible reading of his campaign oratory was that, as President, Bush would be a West Texas version of his father -- an establishment Republican filled with the spirit of noblesse oblige who had promised his own version of "compassionate conservatism" and had turned out to be merely a diligent public servent with no clear sense of political mission."In the final analysis, diligence is probably the last quality anyone might ascribe to our 43rd president, but what matters here is that "compassionate conservatism," which looked so much like a symptom of moderation, was in fact intended as a vector of radical conservatism. And this is precisely the point of Casse's article: "Bush's emphasis on aiding the poor, the disabled, and minorities not only differentiated him from other Republicans but formed the banner under which he advanced what were some truly bold ideas."

What was compassionate conservatism? If it sounded like little more than a focus-grouped public relations slogan, its architects were aware of the charge. In a series of articles published before the election, Bush's domestic policy mentors repeatedly emphasized that, in the words of Stephen Goldsmith, compassionate conservatism was a "coherent, principled philosophy." Or, as Myron Magnet put it in a 1999 Wall Street Journal op-ed, "far from being an empty slogan, it is a well-formed domestic policy agenda."

But what kind of agenda? "At its core," said Magnet, "is concern for the poor -- not a traditional Republican preoccupation -- and an explicit belief that government has a responsibility for poor Americans." But the other notion at the core of compassionate conservatism was that in affirming that responsibility, conservatives could transform the nature of government itself. Goldsmith, a policy advisor to the Bush campaign, wrote that "compassionate conservatism serves as a true bridge from the era of big government as a way to solve social problems to a new era in which we will have a full and healthy trust in the people of this nation to govern themselves." The bridge metaphor is important: in blunter political terms, compassionate conservatism was designed to use the rhetoric of social solidarity to make possible the dismantling of social insurance.

It's perhaps Marvin Olasky (pdf) who presents this equation most clearly. Olasky, commonly described as the father of compassionate conservatism, argues that as long as the public believes that big government helps the poor and limited government does not, voters will choose big government. This is what stands in the way of the longstanding economic conservative dream of truly reducing the size of government. The goal for a compassionate conservative is to use taxpayer money to wean people off of government services. The compassionate conservative believes in using tax dollars to fight poverty -- but it should be done by funneling the money straight into the coffers of local faith-based organizations. The compassionate conservative believes in collecting Social Security taxes -- only to divvy them up and send them right back to individuals for investment in the stock market.

Goldsmith's line about trusting "the people of this nation to govern themselves" reflects the sort of small-is-beautiful attitude that underpins much compassionate conservative rhetoric. Indeed, Olasky's own prose can seem downright anarchist, rhaposidizing about micro-level community organizations taking over from federal bureaucracies. It's also blatantly meant to appeal to religious voters, putting faith-based groups -- even, explicitly, those without any legitimate qualifications -- at the center of its project.

There's too much to compassionate conservatism to unpack here. I'll address some of its major flaws -- and look at its future -- in later posts. In the meantime, I only want to consider what George W. Bush's campaign was attempting to do by embracing Olasky and his fellow-travellers.

For one thing, in the immediate political term, they were trying to get around a brand problem. Casse suggests that the compassionate conservative theme was aimed at "disassociating [Bush] in the public mind from either the confrontational stance of the Gingrich years or the more libertarian impulses of the Reagan era." As he points out, the Bush campaign kept Republican Congressional leaders like Trent Lott, Dick Armey, and Tom DeLay "at arm's length," preferring "a mostly new cast of Republican faces, all apparently selected to emphasize the racial, ethnic, and even ideological diversity of the party."

And this -- like the multiracial cast of the Philadelphia convention -- indicates another of the purposes of compassionate conservatism: to improve the GOP's performance among minority voters. One of the major preoccupations of the Bush circle has been to increase the Republican share of "the black vote" and "the Latino vote"; this goal has informed the Bush administration's decision-making from the very beginning -- as when Karl Rove advised the president to halt the naval practice bombardment of Vieques -- up through the recent battles over immigration. It's not a priority shared by everyone in the party: the Buchananites, of course, want no truck with it, and the immigration fight put the White House sharply at odds with Congressional Republicans, whose district-by-district political calculations were very different. Nonetheless, by helping to address the social concerns -- and religious faith -- of minority voters, compassionate conservatism promised to be an element in this party-building strategy.

It also looked like a way to revitalize the existing conservative coalition, by rearticulating the fusionist logic that had, until recently, held the coalition together. If social and economic conservatives had been drifting apart, compassionate conservatism offered an argument for them to renew their vows: economic conservative ends could be achieved -- could only be achieved -- by social conservative means. Given the importance to the party of evangelical voters and libertarian donors, it seemed a promising arrangement.

Finally, compassionate conservatism was a strategy by which Republicans could move traditionally Democratic issues onto their own turf. Its architects recognized that the GOP simply could not win if it refused to account for the public's interest in Social Security, health care, and education. Compassionate conservatism offered a way for Republicans to engage these issues without betraying their economic conservative base, by emphasizing, in Casse's words, "efficiency, flexibility, and the encouragement of private initiative." This effort, in turn, helped voters see President Bush as "someone like me" -- concerned with domestic matters that mattered to the public yet which had been routinely dismissed by Republicans as little more than fodder for the red pen. The compassionate conservative could say to voters, "I want to improve Social Security and public education." He could, at the same time, say to economic conservatives, "I have a plan for privatizing Social Security and education."

For progressives, the biggest problem with compassionate conservatism is clear: it's essentially a massive pyramid scheme. Basing its "concern for the poor" on an endless series of opportunities to opt out of social insurance, it threatens to undermine social insurance altogether. To economic conservatives, of course, this is meant to be its selling point.

In Casse's early 2001 analysis, this formula looks like a winner:

For how long will voters abide Democratic leaders who remain steadfastly against any use of private accounts for Social Security? How supportive will the public be of Democratic insistence on opposing the use of school vouchers in every case, even for the poorest children? Should the left wing of the party stick to its guns, and should Bush succeed in winning over some centrist Democrats and independents, he may well end up moving these traditionally "Democratic" issues onto the Republican side.Casse sees compassionate conservatism for what it was meant to be: an "ambitious project of realignment." His only worry is that Bush's "reticent and stumbling speaking style" might undermine the president's efforts to make his case.

And that, combined with other trends, could prove a turning point for his party.

Some Republicans still blame Bush's poor communication skills for the apparent failure of compassionate conservatism in the years since 2001. Certainly they've been a factor, particularly in his inability to convince the public to embrace Social Security privatization -- though there's plenty of evidence that the idea itself turns voters off. Moreover, much of the resistance to compassionate conservatism has come from the economic right, who have reeled in horror at the costs associated with the White House's efforts to "transform" Medicare and education. What was once sold as a means to economic conservative ends is now routinely denounced as a disastrous "big government conservatism," which has in turn been made a scapegoat for the Republican defeat in 2006. Meanwhile, of course, events six months after the publication of Casse's article would offer Rove a more potent political weapon, leading the way for Bush's transformation into a "war president."

The White House has never entirely given up on compassionate conservatism. But, having failed to make significant inroads among minority voters, having left fusionism even more ragged than they initially found it, and having lost the confidence of the American public, the compassionate conservatives find themselves isolated in a party whose new crop of presidential frontrunners are likely to ignore them altogether. The irony is that the most promising ideas for what might constitute the next conservatism -- we'll look at them over the next few weeks -- are not too dissimilar from those propagated by people like Olasky, Magnet, and Goldsmith. Given the confusion and strife among conservative ranks, however, those ideas might struggle to find patrons.

The Republican future of March 2001 suggested no catastrophic attacks, no "long wars," no Abramoffs or Abu Ghraibs. Nor did it anticipate just how fractured the conservative coalition would eventually become. In the months after the inauguration of George W. Bush, the Republican future might not have looked particularly bright, but to those who thought compassionate conservatism could offer a way to revitalize the party and the movement, there might have been, at the very least, a sliver of light on the horizon.

Labels: Commentary, compassionate conservatism, George Bush, Reading Conservative History, Republicans

Speaking of the New Republic, this is a must-read. (I know it's considered declasse in the liberal blogosphere to link to TNR these days, but as aggravating as that publication can be, it does often feature worthwhile reporting.)

You may recall President Bush's luncheon (and subsequent private sitdown) with historian Andrew Roberts - a exercise in advanced decadence for certain of the neo-imperialist crowd, who indulged their foreign policy fantasies in a rousing philosophical debate at the White House. Roberts was the guest of honor.

British journalist Jonathan Hari has taken to TNR's website to give us a little more background on Roberts, author of A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900, and - apparently - one of the last true imperialists. Roberts, says Hari, is a man who speaks to white supremacists in Africa, praises British massacres in India, justifies internment in Ireland, and calls on Americans to take up the white man's burden now that the Raj is finished - only he doesn't call it the white man's burden; rather he cites the "Anglosphere." As Hari observes, "The decision to laud Roberts provides a bleak insight into the thinking of the Bush White House as his presidential clock nears midnight."

Roberts's raw imperialism informs the advice he offers Bush today. For one, he urges Bush to adopt a supreme imperial indifference to public opinion. He counsels that "there can be no greater test of statesmanship than sticking to unpopular but correct policies." The real threat isn't abroad, but at home, among domestic critics. Roberts writes, "The greatest danger to [the British and, by extension, the American] continued imperium came not from declared enemies without, but rather from vociferous enemies within their own society."Don't miss the bare-knuckle follow-up exchange between Roberts and Hari, in which the former claims that were the article published in a British journal, it would result in a libel suit. Hari, for his part, gives no ground. At any rate, the dispute focuses on details, leaving unchallenged the issue that the President has embraced the advice of a self-described "extremely right-wing" imperialist, who calls for harsh and unapologetic repression abroad, no matter how much opposition it engenders here at home.

In this Bushian history, democratic debate--especially in wartime--is a sign of weakness to be suppressed. "Contrary to the received view of the Vietnam War, the United States was never defeated in the field of battle," he writes. It was Walter Cronkite, not Ho Chi Minh, who was the true menace: "Some of the media was indeed a prime enemy of the conflict." Self-criticism is only ever interpreted in these histories as "self-hatred," which he says is "an abiding defect in the English-speaking peoples, and for some reason especially strong in Americans." It can only sap the "willpower" of any empire.

It doesn't appear to occur to Roberts that the British or U.S. empires could simply hit up against a limit to their power. Could there be a worse adviser for George W. Bush right now? Roberts's advice is a vicious imperial anachronism: Target civilians, introduce mass internment, don't worry about whether people hate you, bear down on dissent because it will sap the empire's willpower, ignore your critics because they're just jealous, and--above all--keep on fighting and you'll prevail.

Labels: Andrew Roberts, Foreign Policy, George Bush, The New Republic

At MyDD, Jonathan Singer slices out a portion of the latest Bloomberg/LA Times poll (pdf), to make an interesting observation, based on this question:

Q28. In your opinion, should whoever becomes the next Republican nominee campaign on a platform of continuing the policies of George W. Bush, or should he talk about moving the country in a new direction?Singer's comment:

REP L/M CON MEN WOM RELIG Continue Bush policies 30 15 36 31 29 41 Move in a new direction 61 79 54 59 64 48 Don't know 9 6 10 10 7 11

On this retrospective question on George W. Bush and his policies ... Republicans offer a thumbs down by better than a two-to-one margin. Even the religious right, which has gotten much of what it wanted from the Bush presidency (two new hard right conservatives on the Supreme Court for a likely net pick up of one seat for the anti-choice side; federal funds for faith-based initiatives; a curb to funding for stem cell research; a push, however unsuccessful, to ban same-sex marriage; etc.), would prefer the 2008 GOP presidential nominee not be a George W. Bush Republican -- and they remain more supportive of the President than other Republican groups polled.My thought: yes and no. It would be a mistake to read too singular a narrative into these results. Republicans who disapprove of Bush tend to do so either because they're moderates (as shown in the survey) or because they're ideologues who believe Bush hasn't been conservative enough. Undoubtedly a certain amount of this discontent has to do with voters' distress over an era of incompetence, corruption, and war. And in that regard it will be simple enough to hang the Bush presidency around the GOP's neck.

With such numbers, the Democrats' effort to make George W. Bush the 21st century's equivalent of Herbert Hoover -- an albatross for Republicans to carry for several election cycles even after he has left office -- shouldn't be so terribly difficult.

At the same time, don't expect conservative elites to come to the same conclusions. They tend to be fully invested in the "not conservative enough" school - or, at the very least, in the notion that Bush was not politically skilled enough to implement a conservative agenda. Both these lines of thought are actually illustrated by the poll Singer referenced in an earlier post, which compared the attitudes of CPAC attendees toward Presidents Reagan and G.W. Bush. In that post, Singer cited the Washington Wire:

Ronald Reagan is alive and well -- at least, he was at the Conservative Political Action Conference over the weekend. In a straw poll of conference participants, 79% said they would support "a Ronald Reagan Republican" for president, while only 3% said they would support a "George W. Bush Republican." Still, 82% said they favor the president's strategy in Iraq.Singer allows that "these numbers could be as much an indication of respect for Ronald Reagan as they are a sign of disrepect for George W. Bush" - but argues that they nonetheless represent negative attitudes about the Bush presidency that could trickle down to the base. My own estimation would be that the high opinion of Ronald Reagan among conservative elites is directly tied to their discontent with Bush. It's both cause and effect: the more the Bush era fails to redeem the promise of what these elites believe conservative government should achieve, the more Reagan is held up nostalgically as a model for the way things should be. And the more Reagan is valorized, the worse Bush looks by comparison. The CPAC poll was not registering a coincidence, but an ecology of opinion.

Conservative elites do in many ways tend to believe that Bush - Churchillian though he may be - has failed. But they have their own narrative of why and how he has failed, and it has nothing to do with the notion that Bush's conservative policies ruined the country. If any message is going trickle down to the base from the conservative opinion leaders it's this: Unlike Reagan, Bush did not have the political skills or the dedication to implement a truly conservative agenda. This is the message conservative elites will feed into their noise machine, and it's the message that will thus be blasted into the mainstream media as an alternative narrative of the meaning of Bush's failure. And as you'll note, it's a message that ascribes all the disasters of recent years to the president's failure to be effectively conservative enough. It's a message that transforms Bush from albatross to goat.

Labels: conservatives, George Bush, MyDD

(Read Part 1 here)

Michael Novak undertakes a rebuttal of Joseph Bottum's claim that President Bush has been a disaster for the conservative movement. Responding to Bottum's argument specifically, and to conservative "demoralization" generally, Novak plunges us back into the war of perception, beginning with a curious re-interpretation of events in Iraq:

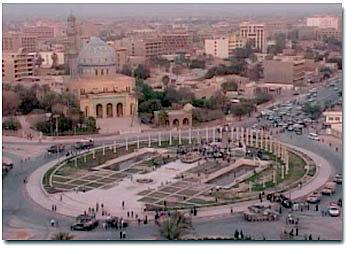

As far as perception of the war in Iraq goes, it’s worth remembering that perceptions are changeable. As the war began in 2003, the New York Times required less than three weeks before it ran a front-page report by a star correspondent of the last generation, R.W. Apple, which hauled out the heavy word of the Vietnam generation, quagmire-as in the quagmire in which, Apple wrote, U.S. troops were already bogged down. Three weeks later, those same quagmired troops had sped into Baghdad, watching as jubilant crowds pulled down the great statue of Saddam Hussein in the center of the city and organizing a systematic search for the suddenly deposed butcher of Mesopotamia.The statue of Saddam, of course, was in fact pulled down by a U.S. military vehicle. There were no "jubilant crowds" at Firdos Square that day - only Western journalists and a handful of militiamen linked to the conman Ahmed Chalabi.

With regard to Apple, Novak appears to be manufacturing a quotation. Novak doesn't cite a source, and my searches haven't turned up any article in which Apple uses the word "quagmire" in reference to the Iraq war, though he did use the term in a 2001 piece about the war in Afghanistan - where, it should be noted, Osama bin Laden remains at large and the Taleban are resurgent five and a half years after the invasion. In an article he'd probably like to forget, Slate columnist Jack Shafer mocked Apple for implying that the Iraq war would turn into a quagmire, but nowhere does the Times reporter appear to have used the word.

The irony, of course, is that Apple's early warnings about Iraq were prescient. For instance, this passage from March 27, 2003:

But the streets and alleys of Iraqi cities are ideal places for urban guerrillas who can blend into the crowds to operate, just as those of Belfast and Tel Aviv have done. Not only are the guerrillas hard to root out, but doing so also works against the American desire to be seen as agents of liberation, not agents of conquest.Or this, from April 6, 2003:

Who is a fedayeen fighter and who is a civilian? Marines tell stories of Iraqis changing in and out of uniform. A civilian bus turns out to be a troop transport. Guerrillas cluster near schools and hospitals. In several cases, troops carrying white flags have opened fire.

Iraqis do not play by the rules of West Point and Sandhurst.

Although the American stay is likely to be shorter [than the British colonial occupation], it could generate the same kind of resentment if not handled with a deftness rare in the annals of triumphant armies. That, in turn, could fuel the kind of resistance to a new government that the United States wishes to minimize, even if Mr. Hussein is killed or captured. It could also further destabilize the Middle East as a whole -- precisely the opposite of what Washington has set out to achieve.Novak's point is to counter Bottum's claim that "the war is already lost" on account of the way it is perceived. "Perceptions are changeable," Novak argues - and he proves his own point by inverting the correct perception of the war.

Still, it is common conservative practice to play the victim when the right's own favored perceptions are insufficiently reinforced in the "liberal media." Novak's response to this challenge is unsurprising: he cites the wisdom of the greatest American conservative leader, who was, not coincidently, an actor:

Ronald Reagan taught us that the perceptions promoted by the liberal media do not, in fact, control the way Americans think. As Clare Boothe Luce once explained, from his experience as a B-movie actor Reagan learned the difference between the box office and the critics. If you win over the first, you can be awfully sweet-tempered to the second. He showed that the hostility of all the liberal media could not, finally, drown out common-sense reality.This analysis begs the question of who represents the box office, and who are the critics. An enthusiastic propaganda campaign might theoretically convince the American public that all is well in Iraq, but will it convince the Iraqis who suffer the effects of the war, or the soldiers who have to fight it?

At any rate, Novak's argument next turns in such a way as to implicitly admit that the problem in Iraq is with the facts on the ground, not with feckless liberal reporters:

I agree with Bottum that in the view of the media the war has been lost. But we may also expect this perception to reverse itself if events in the coming six months unmistakably change direction.Novak asks us to consider what would happen if things really did improve in Iraq: if the Mahdi army were to relent, if al-Qaeda were to flee Baghdad, and if the Sunnis were to see the light and turn against their own insurgent faction. "With these conditions met," writes Novak, "Iraq would come to seem reasonably tranquil." And this may be true, but it's an argument that concedes the weakness of the conservative forces of perception in the face of stiff resistance from reality.

Novak seems unable to resolve his own confusion on this point. On the one hand, he contends that Bush "should have seen, in warfare, the crucial importance of one key goal: victory" (but does this mean that Bush was not seeking "victory" to begin with?). On the other, he acknowledges that "victory" can only be achieved "by bringing security to the people." Again, the conservative impulse to demand a perception of victory runs up against reality's brick wall.

Leaving this puzzle unsolved, Novak turns to Bottum's charge of incompetence, which he suggests is "more troubling." Novak's first reaction is to reiterate an increasingly common conservative fallacy: that the problem is not with Bush's government, but with government itself:

A long-established lesson is that, even in the best of times, government is mightily incompetent—and the bigger government gets, the more incompetent it becomes. Think of how much time it takes to obtain a building permit, to go through vehicle registration, to correct a government mistake on tax forms or on public utility bills, etc. Recall how few government offices in the same building communicate with the others, and how often you are shuttled back and forth.Conservatives have long tried to use the fact that the Post Office lost your postcard to discredit the concept of social insurance and activist government generally, but with the movement's need to escape from under the looming catastrophe of the Bush administration, this argument has gained new urgency. Expectations for Bush were too high, Novak tells us, as though no president had ever governed competently at all.

At any rate, suggests Novak, the tide may be about to turn. He spends the next several paragraphs praising Bush's latest State of the Union address, for its "plain-spoken rhetorical style," its efforts "to occupy what some think of as Democrat [sic] territory," its "simplicity and power" in addressing, once again, the threat of jihad (on this last point Novak asserts that the "stated aim" of the nebulous "Jihadists" is "forcibly to convert us to Islam or to exterminate us until the caliphate stretches around the world" - reason once again to doubt that conservative ideologues in fact understand anything at all about the terrorist threat outside of their own self-aggrandizing fantasies). Novak even cites the post-speech back-slapping as evidence that the address did wonders for the president's popularity.

Unable to resist the conservative appetite for awkward historical comparisons, Novak cites the case of Harry Truman, who was reviled in office but revered in history:

Often enough, the nation’s public leaders have been burned in effigy on the spots where their gleaming statues are later paid respect. If the reputation of President Bush meets such a fate, his 2007 State of the Union address just might be seen as one of the modest pivots on which that turn began slowly to revolve.There's a lot of speculation packed into that "if." Despite the post-address polls Novak cites as evidence of the public's great positive reaction to the State of the Union speech, the latest polls show Bush's approval rating lower than it's ever been.

In the end Novak is forced to rely on the same hope as the president himself: that one day history will, for some reason, judge George W. Bush more kindly. Here's Novak's case:

At the very least, in the face of passionate hostility at home and abroad, George Bush has proved himself a brave and determined man who has staked his presidency on getting democratic momentum underway in the Middle East.What is remarkable here is how, for the president's supporters, the notion of victory in the war of perception mirrors their notion of victory in Iraq: you can't prove that it will never be won - only that it hasn't been won yet.

The debate between Bottum and Novak matters because it will be difficult for conservatives simultaneously to disassociate themselves from the Bush legacy and to argue that that legacy will ultimately prove a positive one. But if you appreciate the irony of fate, you can't help but marvel at how, for Bush and for the conservatives, the struggle against historical judgment looks so similar to their struggle against reality, in the war upon which they have staked so much.

Labels: conservatives, First Things, George Bush, Iraq, Michael Novak

This week's Right-Wing Think Tank Review covered an AEI article by Nicholas Eberstadt and Christopher Griffin which called the recent six-party agreement a "strategic blunder," largely because it failed to address the issue of a North Korean uranium enrichment program, as well as the plutonium weapons the Koreans may have already built.

The foolishness of the neoconservative hard line represented by people like Eberstadt and Griffin is further illustrated by an article in yesterday's New York Times which reports that the White House is publicly admitting that it doesn't even really know if the Koreans have an HEU program. As you'll recall, it was neocon hard-nosing over the HEU issue that prompted the Bush administration to abandon the Agreed Framework in 2002, thus encouraging the Koreans to go ahead and build nukes with the plutonium program that the Agreed Framework had been keeping in check.

Josh Marshall perfectly sums up the horrifying incompetence of it all:

Because of a weapons program that may not even have existed (and no one ever thought was far advanced) the White House got the North Koreans to restart their plutonium program and then sat by while they produced a half dozen or a dozen real nuclear weapons -- not the Doug Feith/John Bolton kind, but the real thing.Absolutely stunning stupidity. The neocons and their pet politicians in the Bush administration have done incalculable damage to American national security and to global stability. As Marshall points out, "In this decade there's been no stronger force for nuclear weapons proliferation than the dynamic duo of Dick Cheney and George W. Bush."

And yet the wheels keep churning at AEI, and people keep pretending to take this crowd seriously.

Labels: American Enterprise Institute, Foreign Policy, George Bush, North Korea

Texas Monthly has an interesting symposium of historians and political hacks on how history will view the presidency of George W. Bush (assuming there's still anyone alive to write history after the presidency of George W. Bush). A notable essay is the one by Michael Lind, which provides a refreshing alternative to the conservative narrative wherein Bush's big spending represents a betrayal of a public that generally supports conservative economic ideas:

IF YOU LOOK AT GEORGE W. BUSH in a larger perspective quite apart from Iraq, you see him as the peak of the post-sixties conservative wave that began with the white backlash against the civil rights revolution. A lot of conservative white Southern and Northern ethnic Democrats who were alienated by racial and cultural liberalism broke away and created, first, a Republican presidential majority and, then, a Republican congressional majority. And yet under Bush, every major conservative proposal of the past thirty or forty years has died—with the exception of tax cuts—because these Reagan Democrats are actually Roosevelt Democrats: They actually like the New Deal. They like the Great Society. They have nothing against Social Security. They want their Medicare. The Republican Congress, in Bush’s first term, passed the Medicare drug benefit, so he presided over the biggest expansion of socialism in the United States since LBJ.Emphasis mine. As I've said before, the Republicans' ability to exploit populist backlashes (racial, religious, and anti-tax) should not be mistaken for the success of any actual conservative ideology.

(h/t: RochesterTurning)

Labels: conservatives, George Bush, Michael Lind

From the Daily Gotham: "Bush's 'surge' is bigger than you think." Could be as many as 48,000 - almost double the number we were first told.

Labels: "surge", Daily Gotham, George Bush, Iraq

(Cross-posted at the Daily Gotham)

Just got back from a nice little SOTU party in Manhattan - I was planning to go to one of the shindigs sponsored by the various New York grassroots progressive groups - including the one I'm part of - but ended up heading to a friend's party instead.

So, unfiltered by media reaction - my own initial thoughts:

It was boring. Bush, who has turned the notion of being a "war president" into a fetish, opened with a tedious - if technically relevant - discourse on domestic economic issues. Within the opening minutes he was talking about earmarks. That'll definitely keep them from switching over to "Best Week Ever."

Nonetheless, Bush presented himself well. He seemed subdued, far less awkward or arrogant than usual. One of the few times I've watched him and not had the distinct impression that somebody quite stupid was actually condescending to me. So props for that.

His health care proposal was a definite wedge. Conservatives seem to be deserting him in droves, but they may be interested in his crappy little health plan. He mentioned "private insurance" more times than I could count. There's no question that his health proposal was designed not for the purpose of getting more people insured, but primarily to reinforce the idea that private insurance is the way forward in health care.

His global warming bit was less than I expected. I mean, it's revolutionary that he even used the term "global warming." So maybe the Kremlinologists can read something into that. I was expecting some discussion of emissions limits. Did I miss that? I didn't hear it.

Jim Webb ate Bush's liver with some fava beans and a nice chianti. I mean, I haven't heard a Democratic response so invigorating since the Bush era began. Sure, Webb came across a little stiff. But his words were fierce. And his conclusion was devastating. Webb ate Bush for lunch.

Now I can read other reactions and see how many people totally didn't see it how I did...

Update: Bush did talk about alternative energy, which I suppose is related to global warming. It's a wood-chips-based future! Anyway, it was mostly a sop to the ethanol lobby. You saw how slobberingly happy Chuck Grassley (R-Where the Tall Corn Grows) looked.

Labels: George Bush, Jim Webb, State of the Union

President Bush's proposal for a health insurance tax deduction could cost millions of Americans their employer-based health coverage. Luckily, as the AP reports, it's going nowhere.

But it does represent a dangerous direction in the health care debate: away from a truly progressive policy and straight into the grasping arms of the insurance industry:

[I]nsurers like the president's focus on health care going into the year.

"With the president coming forward and making health care such a major issue on his priority list, I think progress is definitely possible," [Insurance industry representative Karen] Ignagni said. "We're going to see views and positions from all sides. We see that as a very promising thing. More and more people will come to the view that we've reached a tipping point."

Update: Ezra Klein's take on this is completely different. He sees the Bush plan as a small - but at least positive - step toward uncoupling health insurance from work. I absolutely agree with that as a larger goal, but I'm concerned that this kind of incrementalism - limiting deductions on employer-based care without addressing the need for systematic and affordable coverage - could cause a lot of people to lose care they need now. If this is a "tentative first step" towards real reform, great - but how many people will lose their affordable insurance before we step forward far enough?

Update #2: Ezra says, "I was wrong." So never mind. We all agree it sucks.

Labels: George Bush, Health Insurance

John Fortier of AEI, writing at the Hotline Blog: if Bush forces a "surge," McCain may be damned if it does succeed, and damned if it doesn't.

Labels: George Bush, Hotline, Iraq, John Fortier, John McCain

At the OpinionJournal today, Brendan Miniter discusses how the deepening crisis within the GOP has reached Texas, where the state's House Speaker - and Tom Delay's proxy in the mid-term redistricting caper - Tom Craddick only barely managed to survive a coup attempt led by Democrats and moderate Republicans.

Even deep in the heart of Texas, these days the Republican Party is finding itself divided and on the defensive. Mr. Craddick survived the attempted coup after a protracted fight that dragged into the early evening. But last month seven-term Republican Rep. Henry Bonilla wasn't as fortunate. He was unseated by Democrat Ciro Rodriguez in a special election that grew out of a Supreme Court decision amending the Craddick-DeLay redistricting map. And in November Democrat Nick Lampson defeated a Republican write-in candidate for Mr. DeLay's old seat in the Houston suburbs. Gov. Rick Perry, a Republican, was re-elected, but only after running the gantlet in a four-way competitive race in which he received a 39% plurality. It's no wonder that for nearly two months liberal politicos have been celebrating the end of conservatism.The political map is part of the problem. With the GOP nearly extinguished in the Northeast, and the battleground shifting to the West, the contradiction between the Republicans' coddled Christian fundamentalist base and its increasingly alienated libertarian constituency - the latter being critical to electoral success in the interior West - threatens to tear another hole in the party.

Liberal commentator Jacob Weisberg, writing in Slate in November, went a step further. Positing the end of the "conservative era," he wondered "what will replace it?" He's not alone. Commentators on the right are also wondering what the future holds--it's what happens when a party loses its principles and splits along sectarian lines.

[I]f ... religious conservatives are costing the GOP mountain conservatives, then it's hard to see how the Republican Party avoids a pitched battle for its soul. Values voters lay claim to the last electoral victory for the party--President Bush's re-election in 2004--and Christian conservatives have long had a strong hand in judicial politics on the right. Economic conservatives lay claim to the victories of Newt Gingrich and Ronald Reagan.All of this is developing in two shadows: one growing, the other already long. The first is a Republican presidential primary contest in which all three front runners will be deeply flawed, from the Christian right's perspective, even as each desperately seeks to secure that vital fundamentalist support while not compromising their positions in a general election likely to be determined by voters fed up with the Republicans' long march to the right.

The other shadow, of course, is the war. In what is becoming an increasingly popular metaphor, Miniter reaches back to another Texan president to examine what kind of political damage an open-ended and unpopular war can do.

The last president from Texas who found himself mired in an unpopular war--Lyndon B. Johnson--also presided over a divided party. He left Democrats incapable of capturing the voting public's imagination in national elections, which allowed the GOP to win control of the White House for five of six elections beginning in 1968.Miniter argues that Bush is still attempting to avoid LBJ's fate - and that "winning the war is now a decisive issue."

Which might offer some hope to Republicans, if only Iraq was a war that could possibly be won.

Update: Looking again at this: "Values voters lay claim to the last electoral victory for the party--President Bush's re-election in 2004". While it's true that the gay marriage initiatives drew a late wave of Christian conservatives to the polls - a "surge," if you will - if the lesson that the Republicans take from the 2004 election is that their "values voters" are the key to victory, then the GOP really is on the road to oblivion. But I think that most non-fundy Republican operatives are smarter than that.

2004 was a national security election, through and through, and despite holding the generally insurmountable advantage of wartime incumbency - against a candidate who was systematically demonized as weak - Bush barely eked out a victory. In a normal year, a general election campaign that focused on pleasing the Christian right would go down only somewhat better than one that centered around the demands of the Workers' World Party.

Labels: 2008, Brendan Miniter, George Bush, Iraq, OpinionJournal, Presidential election, Republicans, Texas

Under the command of Alexander, Haslet's Delawares and Smallwood's Marylanders were surrounded by the British grenadier and Scottish 42nd Black Watch. The Brits were amazed at the valor of these two groups. But they destroyed them anyway. Alexander tried to save his troops and ordered an organized withdrawal. Through the Gowanus Creek they withdrew, except for 200 Marylanders led by the war hero, Mordecai Gist. At the Cortelyou House, Gist and his men counter attacked and nearly broke the British lines. Alexander had ordered his sixth counter attack when fresh British troops arrived. And Gist and his fellow Marylanders had to fight their way back to the American Line. Only 9, including Mordecai Gist survived. But the offensive on what is now known as the Stone House, allowed the rest of Alexander's Army to survive. 256 died at the Stone House, [and were buried] in an unmarked grave. [From BrooklynOnLine.com]

Over at Digby's place, poputonian contrasts the desperate gambling of our current Commander-in-Chief to the prudence of our first C-in-C. In September 1776, with the American army in danger of being encircled and destroyed in New York, General Nathanael Green wrote to George Washington urging him to make a strategic withdrawal rather than risk everything in a symbolic stand.

Washington then gathered his generals for a council of war, as Greene had suggested, and revealed the results in a letter to Congress on September 8th:

"On every side there is a choice of difficulties.

...

"In deliberating on this great question [of retreat], it was impossible to forget that history, our own experience, the advice of our ablest friends in Europe, the fears of the Enemy, and even the declarations of Congress demonstrate that on our side the war should be defensive.

"It has been even called a war of posts, that we should on all occasions avoid a general action or put anything to risk unless compelled by a necessity into which we ought never to be drawn. The Arguments on which such a system was founded were deemed unanswerable, and experience has given her sanction.

"With these views, the honor of making a brave defense does not seem to be a sufficient stimulus when the success is very doubtful".

But how would George Surrender-Monkey Washington tell Congress he was going to cut and run? Actually, that part was easy because of who he was:

"I am sensible a retreating army is encircled with difficulties, that declining an engagement subjects a General to reproach, and that the common cause may be affected by the discouragement it may throw over the minds of many.

"But when the fate of America may be at stake on the issue, when the wisdom of cooler moments and experienced men have decided that we should protract the war [by retreating], if possible, I cannot think it safe or wise to adopt a different system."

This was always about America to George Washington, a belief in country that was larger than himself.

There's another lesson to draw from this, though. Washington could afford to retreat, again and again, because time, geography, and the nature of empire were on his side. The Americans didn't lose every battle in the Revolutionary War, but they lost most of them. It didn't matter.

Bush will ask for sacrifice. But the empire will never sacrifice as much as the insurgents, because the empire can leave. The insurgents cannot. The failure of our commanders to grasp this lesson is one of the most fundamental blunders the United States has made in Iraq.

The Iraqi insurgents are no American revolutionaries. I won't speak to what they are, but it's beside the point anyway. There is no military solution before a political solution. It is fundamentally impossible.

And that's what Washington knew, and that's why he won.

Labels: Digby, George Bush, Iraq, poputonian

Josh Marshall on the divine right of George W. Bush.

It reminds me of the thought process that eventually led to my work on this blog: I really do believe that, in certain aspects of modern movement conservatism, we may be seeing the first serious adherents of an American monarchism.

Update: Coincidently, google "monarchism" and this previous post by Marshall comes up on the first page of results. A must-read.

Labels: George Bush, Josh Marshall, monarchism

Shorter George W. Bush:* "In the spirit of bipartisanship and cooperation, I invite the Democratic Congress to kiss my ass."

*Shorter concept blatantly ripped off from Sadly, No!, who blatantly ripped it off from someone else, I think.

Labels: Congress, George Bush, Sadly No

The Old Stone House

The Old Stone House