Saturday, February 03, 2007

The Embarassing Question of Inequality

When forced to talk about inequality, conservatives will respond with two broad claims:

There's no serious dispute over whether inequality is increasing in America. Chait cites the work of Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, which uses tax return data to show that, as Chait describes it, "Since 1980, the share of income accruing to the highest-earning 1 percent of U.S. tax returns doubled, the share of the top one-tenth of 1 percent tripled, and the share of the top one-hundredth of 1 percent quadrupled." Meanwhile, as Paul Krugman recently pointed out, "Median real income was only about 23 percent higher in 2005 than in 1976."

Thus conservatives retreat to their fallback position: Yeah, but so what? Tyler Cowen - drawing on claims by Alan Reynolds - made this argument in a recent New York Times op-ed:

But, as Bradford Plumer explains in another article at the New Republic, it already is threatening the system: it's undermining American democracy:

But economic inequality is also unjust in and of itself, independent of its effects on other institutions. Cowen tries to dance around this conclusion, arguing that, inasmuch as inequality has increased, it has been for innocuous reasons:

The problem for Cowen's argument is that, again, the explosive growth in income has occurred in the top 1 percent of tax filers. Inequality happens most dramatically across the divide between the wealthiest one percent and everyone else. This has nothing to do with the broad segments of the American population that are elderly or educated. Cowen's attempt at bamboozlement is laughable. This is about how a very small number of elites have a massively disproportionate amount of the national wealth compared to the other 99% of us.

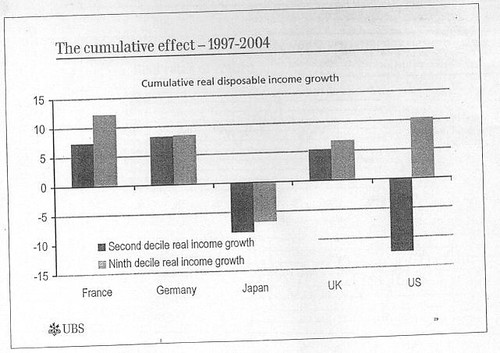

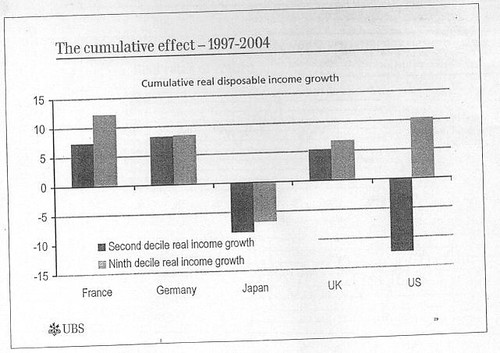

For context, let's look at the graph Jerome a Paris posted at Daily Kos:

Now, this graph expands the upper income bracket to the top 10% of the population, but it still makes a striking point, one that can't be dismissed with excuses about the educated or the elderly - and anyway, don't Europeans have educated and elderly folks too?

A very small number of elites in America have wealth in massive disproportion to the rest of America. Even so: Fine, the conservatives say. That's still not inherently unjust, because it's not a zero-sum game. As long as everyone's boats are being lifted, it doesn't matter if some people's boats go a lot higher than everyone else's.

But it is unjust. As productivity has grown, so has inequality. American workers are making the pie larger, but American elites are getting most of the benefit. The Economic Policy Institute recently reported on this phenomenon:

Conservatives don't want to talk about this, and in recent years liberals have far too often politely obliged. Jim Webb took the gloves off, and it's about time. We have to stop coddling these people.

Judging by a number of remarks I heard throughout the weekend at the Conservative Summit, Jim Webb's response to the State of the Union really grinded a lot of conservative gears. One reason for this is that Webb went hard after an issue that conservatives very much don't want to talk about: economic inequality.

When forced to talk about inequality, conservatives will respond with two broad claims:

- Inequality is not really increasing

- Even if it is increasing, it doesn't matter.

There's no serious dispute over whether inequality is increasing in America. Chait cites the work of Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, which uses tax return data to show that, as Chait describes it, "Since 1980, the share of income accruing to the highest-earning 1 percent of U.S. tax returns doubled, the share of the top one-tenth of 1 percent tripled, and the share of the top one-hundredth of 1 percent quadrupled." Meanwhile, as Paul Krugman recently pointed out, "Median real income was only about 23 percent higher in 2005 than in 1976."

Thus conservatives retreat to their fallback position: Yeah, but so what? Tyler Cowen - drawing on claims by Alan Reynolds - made this argument in a recent New York Times op-ed:

The broader philosophical question is why we should worry about inequality — of any kind — much at all. Life is not a race against fellow human beings, and we should discourage people from treating it as such. Many of the rich have made the mistake of viewing their lives as a game of relative status. So why should economists promote this same zero-sum worldview? Yes, there are corporate scandals, but it remains the case that most American wealth today is produced rather than taken from other people.Ramesh Ponnuru makes the same argument in the February 12 edition of the National Review, which was published to accompany the Summit:

What matters most is how well people are doing in absolute terms. We should continue to improve opportunities for lower-income people, but inequality as a major and chronic American problem has been overstated.

Conservatives generally think that an unequal distribution of wealth and income is not, per se, a bad thing [...]In other words, inequality is not unjust, so it should only be a concern when it has the practical effect of threatening the system itself.

We should care about reducing the number of people living in poverty ... But inequality should matter only if it reaches the point where it threatens popular support for a market economy. It is nowhere near that point. [Print only: p. 22]

But, as Bradford Plumer explains in another article at the New Republic, it already is threatening the system: it's undermining American democracy:

Over the last few years, political scientists have been converging on the view that massive disparities in wealth and income really do distort the democratic process--by allowing a tiny segment of the population to wield outsized influence in the political realm.The wealthy, Plumer points out, vote more (perhaps because they feel the system responds to them), make more political donations (which dramatically increases access to policymakers), and are almost exclusively represented in the ranks of elected officials. The result is a situation in which an activist government actually works for the elites, distributing wealth upwards. This broad imbalance in democratic representation means that some citizens end up being more equal than others. If inequality is left unchecked, "the very idea of 'equal citizenship' will continue its long erosion."

But economic inequality is also unjust in and of itself, independent of its effects on other institutions. Cowen tries to dance around this conclusion, arguing that, inasmuch as inequality has increased, it has been for innocuous reasons:

Much of the measured growth in income inequality has resulted from natural demographic trends. In general, there is more income inequality among older populations than among younger populations, if only because older people have had more time to experience rising or falling fortunes.Thus, inequality comes about mostly thanks to "relaxed bohemians" in their yurts, and old folks unable to stop buying all that crap on HSN.

Furthermore, more-educated groups show greater income inequality than less-educated groups. Uneducated people are more likely to be clustered in a tight range of relatively low incomes. But the educated will include a greater range of highly motivated breadwinners and relaxed bohemians, and a greater range of winning and losing investors. A result is a greater variety of incomes. Since the United States is growing older and also more educated, income inequality will naturally rise.

The problem for Cowen's argument is that, again, the explosive growth in income has occurred in the top 1 percent of tax filers. Inequality happens most dramatically across the divide between the wealthiest one percent and everyone else. This has nothing to do with the broad segments of the American population that are elderly or educated. Cowen's attempt at bamboozlement is laughable. This is about how a very small number of elites have a massively disproportionate amount of the national wealth compared to the other 99% of us.

For context, let's look at the graph Jerome a Paris posted at Daily Kos:

Now, this graph expands the upper income bracket to the top 10% of the population, but it still makes a striking point, one that can't be dismissed with excuses about the educated or the elderly - and anyway, don't Europeans have educated and elderly folks too?

A very small number of elites in America have wealth in massive disproportion to the rest of America. Even so: Fine, the conservatives say. That's still not inherently unjust, because it's not a zero-sum game. As long as everyone's boats are being lifted, it doesn't matter if some people's boats go a lot higher than everyone else's.

But it is unjust. As productivity has grown, so has inequality. American workers are making the pie larger, but American elites are getting most of the benefit. The Economic Policy Institute recently reported on this phenomenon:

Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis through the third quarter of 2006 show that a historically high share of corporate income is going into profits and interest (i.e., capital income) rather than employee compensation. And a newly released Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of household incomes shows that a greater share of this capital income goes to the richest households than at any time since the CBO began tracking such trends. In other words, our economy is producing more capital income and that type of income is more likely to go to those at the very top of the income scale.This, despite what conservatives would like us to believe, is unjust. It is unjust when American workers, the most productive in the world, create additional wealth only for that wealth to be sucked away into corporate profits. If my hard work is rewarded by a situation where my boat rises only a little bit, so that your boat can rise a lot, then an injustice has been done. It is a zero-sum equation.

Conservatives don't want to talk about this, and in recent years liberals have far too often politely obliged. Jim Webb took the gloves off, and it's about time. We have to stop coddling these people.

Labels: Bradford Plumer, conservatives, economics, inequality, Jonathan Chait, The New Republic, Tyler Cowen

Comments:

<< Home

Conservatism is admittedly a fraught term, and I acknowledge that it includes anti-war libertarians as well as evangelicals and neocons. I agree with you in your opposition to the disastrous blunder in Iraq.

I await with interest your forthcoming Wall Street Journal piece, where I presume you'll elaborate on which of your data points your critics don't want to discuss.

Thanks for stopping by.

I await with interest your forthcoming Wall Street Journal piece, where I presume you'll elaborate on which of your data points your critics don't want to discuss.

Thanks for stopping by.

I consider myself a libertarian with some conservative tendencies. Not a trained economist, admittedly, but surely anyone can be unopposed to inequality (in theory) and also aware that indeed some inequalilty IS unjust - what we have now is inequality RIGGED into the way the system works -- which turns some people at the top into beneficiaries of what is essentially rentier capitalism and NOT free enterprise. The ability to distinguish between a theory and its actual practice on the ground is sorely lacking among conservatives, which is why I am a libertarian. It is not necessary to look at charts, even those of Saez/ Piketty. In the last 10 years, I can assure you, a very modest living as a musician, teacher and now writer, went from the middle class (only just) into the underclass. House prices tripled in the area in which I live..in barely 3-4 years; insurance doubled and health.

Those who owned substantial assets won. Those who held savings or did not hold even that lost - massively. Jobs went overseas. A great number of hard working, play -by-the-rules people are just getting by; and a lot of layabouts whose only contribution is to bleed the system prospered. And while as a libertarian and conservative inequality is not a problem to me -- massive inequality DOES in fact become a zero-sum game when it comes to land, water, and anything which is limited in quantity. And that is the middle class. I shudder to think of the difficulty of those at the poverty level with children.

Progressives are famous for having their obsessions with theory at the expense of reality, but conservatives, it seems, do too.

Lila Rajiva

Post a Comment

Those who owned substantial assets won. Those who held savings or did not hold even that lost - massively. Jobs went overseas. A great number of hard working, play -by-the-rules people are just getting by; and a lot of layabouts whose only contribution is to bleed the system prospered. And while as a libertarian and conservative inequality is not a problem to me -- massive inequality DOES in fact become a zero-sum game when it comes to land, water, and anything which is limited in quantity. And that is the middle class. I shudder to think of the difficulty of those at the poverty level with children.

Progressives are famous for having their obsessions with theory at the expense of reality, but conservatives, it seems, do too.

Lila Rajiva

<< Home